For Christmas, Iris got a Lego Egyptian pyramid, complete with a spring-loaded sarcophagus that attacks grave-robbing archaeologists. When you build a Lego model of something, you have to start with the plastic bricks you have available, and the result will be recognizable but with an obvious Lego personality.

In other words, when you look at a Lego model, you say, “Wow, Legos!” When you look at a Greek sculpture, you don’t say, “Wow, marble!”

This is similar to the way the katakana writing system works in Japanese: it takes foreign words and uses Japanese building blocks to synthesize something that is obviously borrowed and obviously Japanese at the same time.

First, a quick recap of the two Japanese writing systems we’ve met so far.

Romaji means Japanese words written with the Roman alphabet. It is the one your Japanese teacher will try to get you to stop using, because it’s brain-rotting training wheels.

Hiragana is the syllable-based character set used to write certain simple words. It is also used by children and novice students of Japanese (hello!) to write everything. When you succeed in learning hiragana, which doesn’t take more than a week or two, you’ll feel like you’ve accomplished something. You have accomplished nothing. (How is this drill sergeant zen master routine working for me?)

Katakana is hiragana’s evil twin. The name reminds me of the classic 80s computer game Karateka, in which a black-belt karate master tries to learn the four Japanese writing systems and gets so mad he just goes around kicking people. Like hiragana, katakana has 46 characters, and each character represents a legal syllable in spoken Japanese. But katakana is used to write different stuff. No, really. It’s as if we had one English alphabet for writing some words and another, Dr. Seussian, alphabet for writing other words.

Katakana’s main raison d’être is writing foreign words and loanwords. (I don’t know if “raison d’être” is something they say in Japan, but if it is, it would be written in katakana.) When I took French, we learned that France has a snooty (even by French standards) government department charged with maintaining the purity of the language and defending it from foreign interlopers like le meeting and le weekend. This effort has mostly failed, of course, but there have been occasional successes, like “l’ordinateur” for “computer,” instead of, perhaps, “le computeur.”

Japan hasn’t even tried. Japanese is so full of English words, it reads like a bicultural ransom note. Those English words, along with some assorted French, German, Portuguese, and recently borrowed Chinese words, are rendered in katakana. For example, here’s how you say “computer” in Japanese:

コンピュータ

which is pronounced “konpyuuta.”

But katakana’s responsibilities don’t end there. My katakana workbook, Let’s Learn Katakana, explains that it’s also used for onomatopoetic words (Japanese has many of these), sometimes for the names of plants and animals, and most important: for writing domestic telegrams. (Let’s Learn Katakana was published in 1986.) Also, sometimes people write words in katakana just to look cool. You know, like how Americans use Comic Sans.

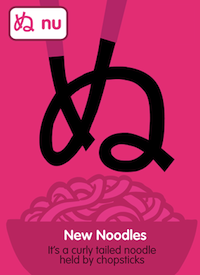

The good news is that katakana is very easy to spot. You will practically never look at a word and wonder whether you’re reading hiragana or katakana, because one is sinuous and the other is jagged. Here, side by side, are the hiragana and katakana for “ma”:

㾠マ

If it’s cuddly, it’s hiragana. If it looks like ninja weaponry, it’s katakana.

Now, back to those English loanwords. It’s hard to fathom just how many thousands of English words have made their way into Japanese, from “aisu kurÄ«mu” (ice cream) to “zero.” A huge section of Let’s Learn Katakana is devoted to recognizing and writing these words, and I didn’t understand why until I started paying closer attention to Japanese packaging and labels. (Incidentally, Japanese packaging and labels are the world’s best; the Japanese invented frustration-free packaging back when Amazon was just a river.)

The other day, for example, I was doing some laundry and noticed a shirt with a label that said エディーãƒã‚¦ã‚¢ãƒ¼. My brain clicked over into Japanese mode. (Is it a sign of progress when you can feel your brain switch gears like an automatic transmission?) Written in romaji, that would read: “ediibauaa.” Eddie Bauer!

Meanwhile, Iris peered at another label and saw ナイãƒãƒ³. That’s “nairon,” i.e., nylon.

Katakana and Japanese loanwords make me a little queasy, because if you’re an English speaker committed to speaking Japanese well, you’ll spend a considerable amount of time essentially speaking English with a stereotypical accent. I asked my teacher, Toshiko Smith of the Seattle Japanese Language School, whether I could tell people in Japan that I’m from “Seattle,” instead of having to say シアトル (Shiatoru). Sorry, said sensei: if you want to be understood, use the Japanese pronunciation. Indeed, in Japan, Ms. Smith would be known as スミスã•ã‚“ (Sumisu-san).

Because, you see, Western names are also written in katakana. Here’s mine:

マシュー

There’s no “th” sound in Japanese, so it’s pronounced “MashÅ«.” I’m not sure how I feel about this. Is it too late for me to choose an alias like ターミãƒãƒ¼ã‚¿ãƒ¼ã•ã‚“?