Japanese has four writing systems.

Let me say that again: Japanese has four writing systems. If you want to read and write it fluently, you have to learn four writing systems. This is like being told that if you want to pass the driving test, you will have to build a car from scratch, and that car will have to pass California emissions standards.

Luckily, of the four systems, you get one for free if you’re literate in English. This one is called romaji, and it’s used to write Japanese names and other words using the characters of the Roman alphabet. When you see “konnichiwa,” that’s romaji. It’s blessedly common to see place names written in romaji on signs in Japan, but it’s certainly the least used of the four systems.

When you were a kid, did you ever create a secret code where you replaced letters with simple shapes and could thereby pass notes to your friends without, well, I’m not sure who we thought was going to spy on our mail. Parents? Cops? Rival ninjas? In your home-cooked code, maybe A turned into a circle and B a bunch of wavy lines.

That cipher you created is something like hiragana. Hiragana, for reasons I’ll get to soon, isn’t literally an alphabet, but it is literally and figuratively loopy.

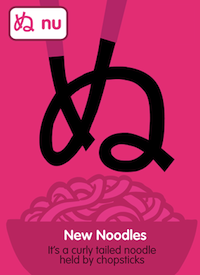

Let’s meet hiragana. Here’s an actual character:

ã¬

That one is pronounced “nu,” and it’s one of my favorites. Hiragana books tend to teach mnemonics for memorizing the characters. The one I used, Hiragana Mnemonics by Bob Byrne (actually, I used the [app](http://itunes.apple.com/us/app/dr.-mokus-hiragana-mnemonics/id387585135?mt=8)), says “nu” looks like a pair of chopsticks trying to capture an errant NOOdle. “Nu” for “noodle.” Not bad. This is one of the easier ones to remember.

As with any mnemonics, the dumber they are, the better they work. I initially dismissed Byrne’s mnemonics and said to myself, “I don’t need a crutch to learn a few characters,” and then found that, gosh, it’s hard to forget that the “mu” character (ã‚€) looks like a farting cow.

During the two weeks or so that it took me to learn the 46 characters of hiragana, I found myself thinking over and over that it’s funny how our English alphabet is so logical and straightforward, and this Japanese one is a hodgepodge of squiggly goofs. More specifically, I reasoned, our letters look like the sounds they make. I mean, an M looks like it should make the “M” sound, right? Whereas in hiragana, this thing:

ã¾

is supposed to sound like “ma.” Ridiculous!

Intellectually, I know that this is absurd. Our glyphs are just as arbitrary as theirs, although when I take a break from Japanese practice, shake off the wiggly weirdness of hiragana, and look back at the Roman alphabet, I start to notice some oddities, like the fact that you form your mouth into an O to speak the letter O.

My friend Neil has been to Japan several times, so I bragged to him that I’d learned all my hiragana. He’d learned the characters, too. “But I never got to the point where it looked like words,” he added.

Way to spoil my moment, dude. Fluent readers, in English or any other language, don’t read words letter by letter. We don’t sip. We gulp down whole words and sometimes whole phrases as single units. But hiragana doesn’t look like words to me yet. It still looks like code.

A couple of years ago, when Iris was in kindergarten, I spent an afternoon every week volunteering in her classroom. Seattle public schools use a “writer’s workshop†curriculum, where students in every grade are expected to write every day. This includes kindergarteners, who have a wide range of writing abilities, ranging from “can write†to “wouldn’t recognize the letter P if it peed on them.†I spent a lot of time helping kids try to recall which letter makes, say, the “K†sound. I did my best to empathize with the difficulty of the task, but remembering back to a time when I didn’t know the alphabet was simply beyond me.

Well, that nightmare about being back in school has turned real. Recently I woke up at 4am and couldn’t get back to sleep until I remembered the hiragana that makes the sound “ho.†(It’s ã».) When I read hiragana, I sound exactly like a tentative five-year-old sounding out a word. (Incidentally, I frequently have the nightmare where I forgot to go to class all year and now have to take the final exam. I do not, however, sit bolt upright in bed, dripping with sweat, when I wake up from it.)

Even if I get to the point where hiragana looks like words, I have another problem: most words in Japanese aren’t written in hiragana. Four writing systems!

I realize I’ve said little about how hiragana actually works, and how and when you use it to construct words; that oversight will soon be remedied at length.